Samantha Sawhney

Although early Hindu mythology seemingly lacks strong resonance with that of the Judeo Christian tradition, the myth of Manu (मनु) and Matsya (मत्स्य) found in the Mahabharata (महाभारतम्) and Satapatha Brahmana (शतपथब्राह्मणम्) shows striking similarity with the flood of Genesis 6, demonstrating cross cultural commonality and distinction between early Hindu thought and early Judeo Christian ideals.

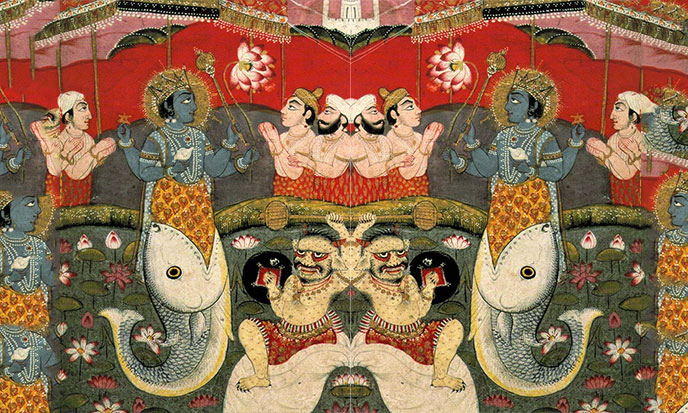

The word Matsya literally translates to fish in Sanskrit and Matsya himself first appears in the Satapatha Brahmana where Matsya seeks protection from Manu as small fish:

“A fish came into his [Manu’s] hands. It spake to him the word, ‘Rear me, I will save thee!’ ‘Wherefrom wilt thou save me?’ ‘A flood will carry away all these creatures: from that I will save thee!’” (Satapatha Brahmana 1.8.1.1-2).

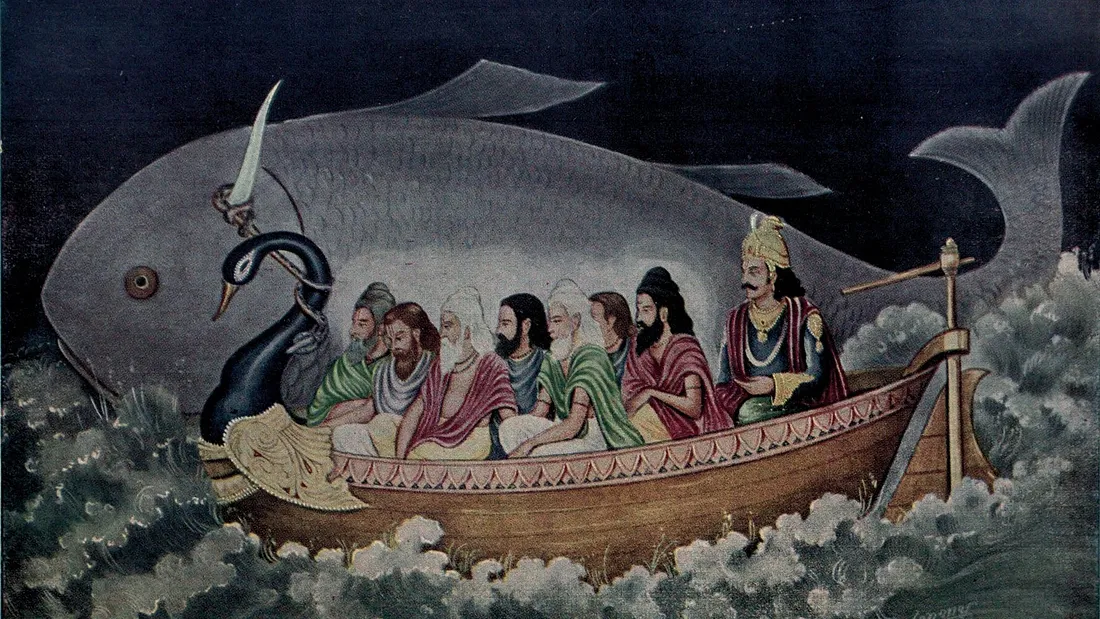

As seen above, the god is vulnerable and sincere in his petition to Manu and offers him a boon to incentivize his protection. In later Hinduism, the fish deity is understood as the first avatar of Vishnu (विष्णु) in a sequence of ten divine incarnations or avatars (अवतार) on Earth (Britannica-“Matsya”). Manu survives the flood and is pulled to safety by Matsya to found a new society.

The flood myth found in chapters 6 to 9 of the book of Genesis (בְּרֵאשִׁית), the first book in Torah (תּוֹרָה), recounts the story of Noah, who was picked by God to survive a flood meant to destroy humanity entirely for their wickedness. God then commissions Noah to build an arc to preserve animals and peoples’ of the Earth. Noah boards his arc and weathers the storms to repopulate society, but conflicts arise among his sons.

Both Manu and Noah are selected to survive flood events engineered to destroy mankind and are commissioned to build a vessel to survive it. The threat of mass extinction as posed to the men forces them into absolute dependency on an elusive semi-divine figure. In the Satapatha Brahmana, Matsya is not fully understood as divine only make the transition from Matsya, a fish, to jhaṣa (झष), a large fish. Later Hindu scriptural traditions cast Matsya as an avatar of Vishnu, but that is not articulated in the myth’s earliest iterations. Therefore, the role of divinity in Manu’s deliverance is unclear. Genesis is more direct with the nature of Noah’s deliverer. It says, “God said to Noah: I see that the end of all mortals has come, for the earth is full of lawlessness because of them. So I am going to destroy them with the earth.” (NABRE Gn 6:13). There is no ambiguity in the fact that God is the reason Noah survives the flood and that he is interfacing with the divine.

The distinction in the nature of salvation from the flood shows a discrepancy in both the roles of the nature and the divine. Matsya can be seen as an emissary of nature’s intangible divinity, protective when it is protected, but lacking in generosity. Manu’s survival is dependent on his ability to protect a vulnerable animal. On the contrary, the reasons for Noah’s salvation are unclear and contradictory. It says, “Noah found favor with the LORD” (NABRE Gn 6:8) and “Noah was a righteous man and blameless in his generation” (NABRE Gn 6:9). It is not clear why Noah is chosen to survive and repopulate the Earth, exhibiting a profound differentiation in the nature of the law of divinity. In this particular Vedic story, hierarchy is the means of communication for both Manu and Matsya. In contrast, God’s logic is not apparent to Noah or the reader, but the reasoning for the flood is elaborated as “the wickedness of human beings” (NABRE Gn 6:5).

Therein lies a profound difference between Vedic and Judeo Christian religious rhetoric. While Vedic figures have reason and natural hierarchy behind their actions, nature and divinity lack logic. Judeo-Christian discourse has an inverted approach the reason for actions are not clear, but the violence is not senseless as it is in the Satapatha Brahmana. The violence of reality is existence is fully realized whether it is arbitrated through hierarchy or divinity.

To conclude, the common flood myth in the book of Genesis and the Satapatha Brahmana is indicative of both shared ideals and disharmonies within the texts. The nature of salvation remains consistent in the way a person needs to actualize it. Noah must build the arc and Manu must build a boat, and both are the chosen men to repopulate the Earth. The texts differ in their approach to the justification of violence and the actions of divinity. Both texts are not only microcosmic instances of a flood, but also indicative of larger cultural religious themes and harmonies. It is not only the existence of a flood myth, but also the content of the myths that is revelatory of the similarities and key differences with the two texts.

Works Cited

The Bible. New American Bible, Revised Edition.

Eggeling, Julius, translator. The Satapatha-brâhmana: According to the Text of the Mâdhyandina School: Books I and II. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 2007. Wisdom Library, www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/satapatha-brahmana-english/d/doc63144.html. Accessed 18 Jan. 2023.

“Matsya.” Britannica School, Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 Mar. 2015. school.eb.com/levels/high/article/Matsya/51430#. Accessed 18 Jan. 2023.

Great job in parsing information, connecting the dots and developing this educative piece; thanks.

Great job in parsing information, connecting the dots and developing this educative piece; thanks.

q6cxxl

Good post. I definitely appreciate this website. Stick with it!

Good post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon on a daily basis. Its always exciting to read content from other authors and use a little something from other web sites.