by Abram Haynes

It’s hard to make history. It’s hard to fuel empires, to create empires. It’s hard to leave a legacy. Nevertheless, the Punic Wars did this all. From 264-146 B.C.E (Bagnall 9-10), these conflicts wracked the Mediterranean world. When the dust finally settled, Rome was no mere federation. It was a superpower.

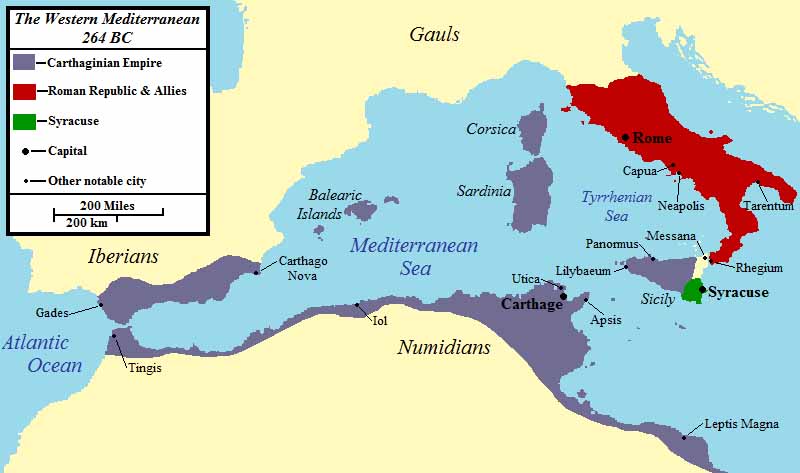

The term “Punic” stems from the Greek word for the Phoenicians (Lambert), seafarers who founded Carthage as a colony (Lendering “Phoenicians”). The Wars featured two main players: the rising Roman Republic, fresh from Italian expansion (Wasson), and Punic Carthage, an “informal” trade empire in North Africa (Lendering “Punic”).

Like much history, competing interests bred conflict – in this case, Rome’s imperial aims in Sicily, a place dominated by Carthage (Bagnall 35). This article’s focus is the First Punic War, from 264-241 B.C.E (Cartwright). With its end, Rome acquired its first overseas territory: Sicily (Brooks).

The Mamertines, Sicily, and the War’s Beginning

The war sparked when mercenaries, called the Mamertines, captured the city Messene, in northeast Sicily (Polybius 1.7.1-11). For context, Sicily looks like a sideways witch’s hat, with the Italian boot striking its tip. Because Hiero II of Syracuse, in Sicily’s southeast, hated the Mamertines, he met and defeated them in 265 B.C.E (Lendering “Mamertines”). In response, the mercenaries sought aid from both Rome and Carthage (Polybius 1.10.1-2).

Carthage sent a garrison, but Rome hesitated (Bagnall 34-35). Years prior, they had crushed similar mercenaries in Italy, men who had also seized a city (Bagnall 35). Helping the Mamertines felt…fickle (Polybius 1.10-3-4). Nevertheless, imperialism made the choice – Rome headed for Sicily (Bagnall 36).

When Consul Appius Cladius arrived with his troops, he defeated both Carthage and Hiero, then marched towards Syracuse (Lambert). Many cities joined Rome (Polybius 1.16.3), and Hiero read the room – he, too, aligned with the Republic (Cartwright). The war was on.

Early War in Sicily

By 262, Carthage had a mercenary army in Sicily (Bagnall 36), and Rome besieged the city Agrigentum, also called Acragas, (Cartwright) on Sicily’s southern coast. The Carthaginians retreated by night (Bangnall 36), letting Rome ravage the city (Polybius 1.19.14-15). For these first three years, ostensible Roman strategy had been aiding the Mamertines (Bagnall 38), but this evolved. The Republic wanted Sicily; they were ready to bleed for it (Polybius 1.20.1-2).

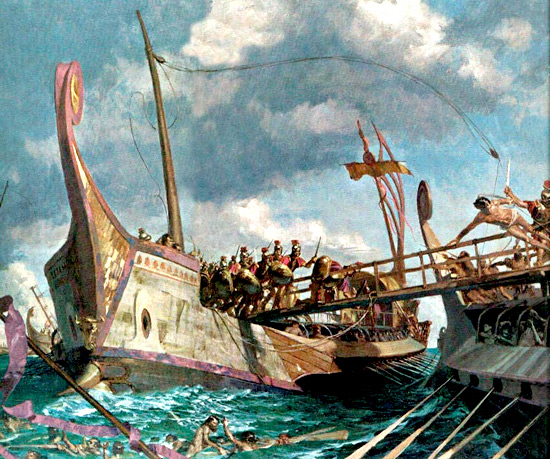

They would. The war turned sluggish, with Rome’s sieges hindered by Carthage’s strong navy (Bagnall 38). To break this, Rome – a landpower – built a naval fleet (Polybius 1.20.8-9). As Polybius said, the First Punic War is why “the Romans first took to sea.” (1.20.8)

And that they did: in mere 60 days, Rome constructed 120 ships (Cartwright), likely using a wrecked Carthaginian craft as a model (Polybius 1.20.15) Given the technology, it was quite the feat.

Despite initial setbacks (Bagnal 38), Rome achieved a stunning naval victory at Mylae in 250 (Bagnall 39). It was here, off northeast Sicily, that Rome introduced the corvus (Cartwright). This device was a mobile gangplank, which latched to enemy ships and let infantry board (Lambert). Like that, Rome brought their soldiers to the waves (Cartwright). The Mediterranean had a new contender.

Rome in the Water

In 258, Rome scored victory at Sulcis, in Sardinia (Cartwright), but Sicily stayed contested (Cartwright). As Nigel Bagnall suggests, the Romans failed to centralize on a single, absolute objective, resulting in limited gains all around (Bagnall 39).

It is no surprise, then, that their strategy shifted. Rome settled to invade Africa, hoping to endanger Carthage directly (Polybius 1.26.1). The result was “one of the largest naval battles in history” (Bagnall 39): the Battle of Economus.

It was summer, 256 B.C.E (Cartwright), when consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius (Polybius 1.26.11) met Carthage south of Sicily; after a convoluted battle, Carthage was forced to retreat (Cartwright). Africa was open (Bagnall 40). Counting by manpower, Economus may be history’s largest sea battle, with 140,000 Romans and 150,000 Carthaginians participating (Lambert). Following necessary repairs, Rome landed east of Carthage. (Polybius 1.29.1-3).

Fighting in Africa

Consul Regulus saw half his forces recalled (Lambert), possibly due to logistics – there had been some 75,000 rowers to feed (Bagnall 41) – but still managed several victories (Cartwright). In fact, these even prompted peace talks (Polybius 1.31.1-8). However, Regulus’s demands were very harsh, and negotiations soon collapsed. Coupled with local African revolts, Carthage’s future looked bleak (Polybius 1.31.2-3). At least, until Xanthippus arrived (Cartwright). Fighting for Carthage, this Spartan mercenary connected the recent defeats with poor leaders, not bad soldiers (Bagnall 41). Xanthippus reorganized his forces, decisively defeating and capturing Regulus in 255 B.C.E (Lambert). The Republic lost 12,000 soldiers; Carthage lost 800 (Cartwright). Rome scrambled to evacuate the survivors (Bagnall 41).

Rome repulsed a Punic fleet, collected Regulus’s men, and headed for Sicily (Polybius 1.36.11-12). They would not make it. Off Camerina, near southern Sicily, a tempest decimated the returning ships (Bagnall 41), with deaths possibly reaching 100,000 (Cartwright). It’s a useful microcosm for the war itself. That is, a vicious slog, where nations were beaten senseless only to keep struggling – and that’s just what happened next.

The Republic replaced the lost fleet, augmenting its survivors then storming Panormous (Polybius 1.38.5-10), in Sicily’s northwest (Bagnall 38). As more cities joined Rome, Carthage grew largely confined to west Sicily (Bagnall 42). Following a raid in Libya, however, another Roman fleet was again decimated by storm (Bagnall 42), possibly due to the corvus – its bulk could be unwieldy (Cartwright) – and the device was later phased out (Bagnall 43). These appalling losses saw Rome limit its navy, reluctantly returning to land (Polybius 1.39.7).

The Slog Continues

In 251 (Cartwright), a Carthaginian expedition held the area around Lilybaeum, a city in west Sicily, for around two years (Bagnall 43). Success ended at Panormus (Bagnall 43). In this battle, powerful Punic elephants were lured towards Panormus’ walls, where they were bogged down and routed (Polybius 1.40.1-16).

Despite this victory, one thing was clear: dominance in Sicily required ships. The Republic reinvested in its navy (Bagnall 43), then besieged Lilybaeum (Polybius 1.41.4). This was one of Carthage’s last Sicilian strongholds, and each side knew it well (Polybius 1.41.4-5). Consequently, the ensuing siege was savage, interminable, and inconclusive – when the war ended, years later, Lilybaeum had never surrendered (Bagnall 43). Like Rome, Carthage had guts. Like Carthage, Rome’s leadership could – and would – make mistakes.

Rome faced the Punic fleet at Drepana, near Lilybaeum, (Bagnall 43) in 249 (Cartwright). Before battle, consul P. Claudius Pulcher hurled his sacred chickens overboard, as they wouldn’t promise victory by eating – he supposedly invited them to drink (Lambert). At Drepana, Pulcher was humiliated (Bagnall 43), with 93 of 120 ships being captured (Cartwright. The consul himself escaped (Polybius 1.51.11). Around the same time, another Roman fleet, including 800 transports, was gutted in bad weather (Bagnall 43). The double loss saw Rome concede the sea, refocusing, once more, on land (Polybius 1.55.1-2).

By then, it had been roughly 17 years of conflict; the American Revolutionary War lasted 7 years. Both sides were understandably exhausted, with Carthage’s treasuries so depleted they asked Egypt for a loan – the Nile-born kingdom refused (Cartwright).

Hamilcar, Fatigue, and the End of The First Punic War

Nevertheless, Hamilcar Barca, Hannibal Barca’s father, successfully raided Italy’s coast in 247 (Cartwright). He deployed in Sicily, next, but could only wage a guerrilla war – dry coffers and shifted interest meant few funds (Bagnall 44). Hamilcar was talented, however, and his chaotic attacks were often triumphant; with more support, he likely could have done more (Lambert). According to Polybius, there were numerous small-scale skirmishes, but nothing “decisive” (Polybius 1.57.7).

The stalemate again forced Rome to water (Polybius, 1.59.1-3), and by 242 a new fleet was funded by private citizens (Cartwright). Sources differ, but the general consensus cites blockade as Rome’s objective (Cartwright) (Polybius, 1.59.4-5) (Bagnall 44). The Punic fleet, which had previously withdrawn, rushed to relieve their men (Bagnall 44). The sides met at the Aegates Islands, near western Sicily (Lambert), fighting a brutal engagement which Carthage lost (Bagnall 44). The year was 241 B.C.E (Cartwright), and Carthage was through (Polybius 1.62.1-2). They had fought long and hard, but their army was trapped (Polybius 1.62.2), and their economy was bleeding (Cartwright). The war was over.

The stranded Hamilcar gained negotiating permissions (Polybius 1.62.3), accepting a bitter treaty in 241 (Lambert). Under the terms, Carthage lost Sicily and owed Rome 3,200 silver talents as indemnity (Cartwright). With that, the battered Punic traders retreated, replaced by bloodied but victorious Romans. Sicily, as mentioned, was the Republic’s first overseas territory (Cartwright), won by a virulent, 24-year slaughter (Polybius 1.63.4). It took a generation, but the First Punic War had ended.

Of course, history is organic; it’s not a simple line, but complicated and overlapping, rarely just “stopping.” Frankly, “peace” was subjective. Carthage immediately faced mercenary rebellion, Rome fought Gaul and Illyria (Bagnall 44-46), then tore Sardinia and Corsica from Carthage (Brooks). For this article’s sake, however, we will end here: Carthage is diminished, Rome is growing, and the scene is set for Hannibal Barca and the Second Punic War (Cartwright).

Works Cited

Bagnall, Nigel. The Punic Wars: 264-146 BC. Edited by Professor Robert O’Niel. 7th Impression, Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2002.

Brooks, Christopher. “9.6: The Punic Wars.” LibreTexts. LibreTexts, 17 Sep. 17 2019. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/History/World_History/Book%3A_Western_Civilization_-_A_Concise_History_I_(Brooks)/09%3A_The_Roman_Republic/9.06%3A_The_Punic_Wars/. Accessed 2 August 2022.

Cartwright, Mark. “First Punic War.” World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 26 May 2016. www.worldhistory.org/First_Punic_War/. Accessed 21 August 2022.

Lambert, Kelly. “The Punic Wars: Part I.” The Kosmos Society, Harvard University, July 29 2021. https://kosmossociety.chs.harvard.edu/the-punic-wars-part-i/#sdfootnote16sym. Accessed 1 August 2022.

Lendering, Jona. “Mamertines.” Livius. Livius, 2006. www.livius.org/articles/people/mamertines/. Accessed 2 August 2022.

—. “Punic Carthage.” Livius. Livius, 2004. www.livius.org/articles/place/carthage/. Accessed 1 August 2022.

Polybius. The Histories of Polybius, Volume I Translated by W. R. Paton, Loeb Classical Library, 1922. LacusCurtius.https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Polybius/1*.html Accessed 21 August 2022.

Wasson, Donald L.. “Roman Republic.” World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 07 Apr 2016. www.worldhistory.org/Roman_Republic/. Accessed 1 August 2022.