Samantha Sawhney

What does the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Sanskrit religious epic about Vishnu’s reincarnations, have in common with Jorge Louis Borges’s 1945 short story “El Aleph?” The commonalities are not obvious, but upon closer examination, one would encounter distinct similarities in their discussions of experiencing divinity in complicated circumstances.

The Bhagavad Gita is one of the most widely known and translated Sanskrit works. It narrates the dialogue between an incarnation of Vishnu, Krishna, and an archer, Arjuna, in a larger metanarrative– the Mahabharata. Moreover, though Krishna’s explanatory statements dominated the passage, this dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna is recounted by a king, Dhritarashtra, and his secretary, Sanjaya, laying the theological framework. It is a compact summation of amassed Hindu theology. Within this discourse, Krishna reveals his highest self or ‘true form’ to Arjuna.

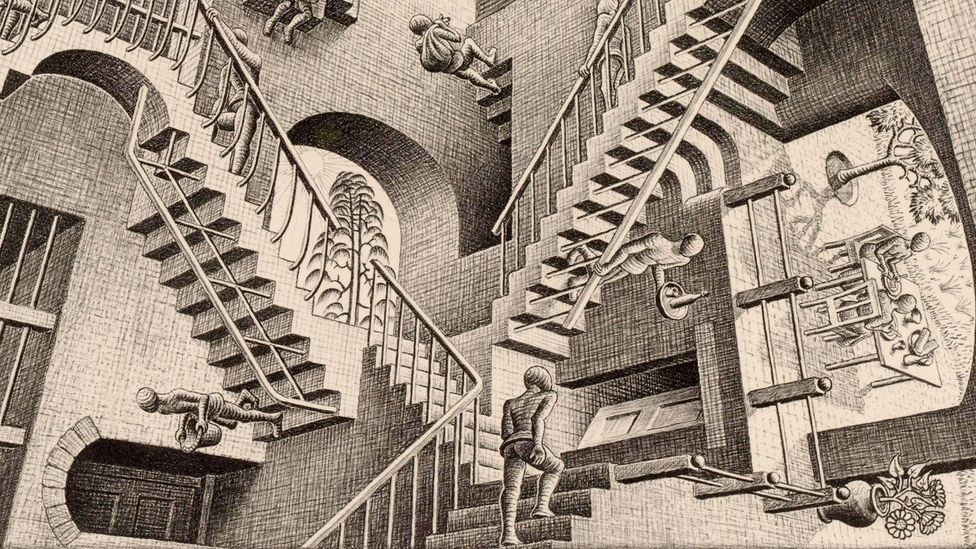

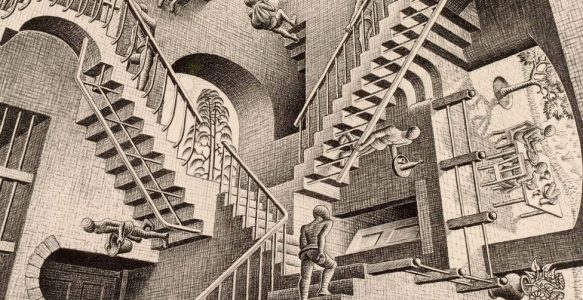

On the other hand, “El Aleph” is a short story from Borges’s collection of the same name. It is narrated by a fictionalized version of the author who builds a close, yet strained relationship with the cousin of his deceased lover, Beatriz Viterbo. Her cousin, Carlos Argentino Daneri, is a struggling poet, seeking to write an epic poem depicting the totality of the Earth, aptly called “La Tierra”. As the story progresses and tensions increase between Borges and Daneri, the latter reveals his aleph– “one of the points in space that contains all other points” –and uses it to compose “La Tierra” (Borges 6).

The revelation of the aleph and Krishna’s expression of his highest form to Arjuna are both encounters with what can be termed as the ”godhead.” Initially, the divine must be accessed from a suspension of realism and acts of trust. For Borges, it is venturing into the basement of Argentino Daneri where he, “let [himself] be locked in a cellar by a lunatic” (Borges 8). And for Arjuna, it is being in discourse with Krishna and asking the god, “to see how You have entered into this cosmic manifestation… to see that form of years” (Bhagavad Gita 11.3). This risk-taking act of trust enables a greater vision to be attained for both Arjuna and Borges. Krishna states, “I am the source of everything; from Me the entire creation flows” (Bhagavad Gita 10.8). While this declaration is general, it encompasses the feeling of a greater creative fount from which all things originate. Borges describes a similar phenomenon within his story, “[i]n that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful” (Borges 8). Therefore, the divine is generally and conceptually infinite. Then divinity contains more specificity, not just an overwhelming everything, but an experience that has distinct describable faucets. For example, Arjuna states, “I see in Your [Krishna’s] body all the demigods and different kinds of living entities, assembled together” (Bhagavad Gita 11.15). This matches Borges’s statement that “[e]ach thing (a mirror’s face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe” (Borges 9). This compounding of figures and ideas into a collective that maintains their distinct identity is a strong commonality shared by the two works.

Besides similarities, there are also several distinct differences in Borges’s account of the godhead when compared to that of the Gita. Firstly, Borges’s divine encounter is fundamentally interpersonal as he says, “I saw a woman in Inverness whom I shall never forget … I saw a monument I worshiped in the Chacarita cemetery” (Borges 9). Through repetition, Borges emphasizes that his experience entails other people and goes so far as to address the reader, saying, “I saw your face” (Borges 9). The reader becomes a part of the story as well as the mystical unknown, divorcing the story from the vague context and time in which it is set. His vision also relates deeply to the narrator’s life, as the monument he worships is the grave of Beatriz. What is most significantly different between the two, is the effect the visions have on the men. Borges feels, “infinite wonder, infinite pity” (Borges 10), while Arjuna describes the shape as, “glowing effulgence, which is fiery and immeasurable like the sun” (Bhagavad Gita 11.17). His words speak of reverence, while also speaking of fear. Arjuna fears this godhead the totality of all human experience he has witnessed, Borges, instead, feels wonder and pity, which is a stark contrast to Arjuna.

This comparison raises questions for future research: How do we experience divinity? How is that affected by human experience and nature? What language do we use to circumscribe God? Both Borges and the Bhagavad Gita offer us means to discuss divinity, and yet the effects are unclear. Borges remains a cynical and jaded writer and Arjuna begins a siege on his brethren. It is as if one can see God or the universe and remain largely unchanged, operating in a similar way as they did before the encounter. Then, does human nature overpower glimpses of divinity?

Works Cited

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda,, translator. Bhagavad-gītā as It Is. Complete ed., rev. & enl. ed., Los Angeles, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1983.

Borges, Jorge Louis. The Aleph. Translated by Norman Thomas Di Giovanni, e-book ed. PDF.